According to the “Additive Manufacturing in Military and Defense 2024” report by AM Research, direct U.S. DoW spending on 3D printing and AM is estimated to exceed $2.6 billion by 2030. There are numerous examples of the technology being used for military and defense applications, and you can learn more about this at our upcoming Additive Manufacturing Strategies event in New York City. But, just because it’s the military using AM, doesn’t necessarily mean it’s all for weapons or defense readiness.

Hill Air Force Base, located in northern Utah, is one of the top installations of the United States Air Force (USAF). The base has been using 3D printing for several years, creating replacement parts for the F-22 and F-35 fighter planes. It’s also home to the Hill Aerospace Museum, which is dedicated to the history of the base and aviation in Utah. 70 aircraft and thousands of historical Air Force artifacts are on display at the museum, and its technicians are now using 3D technology to help preserve aviation history.

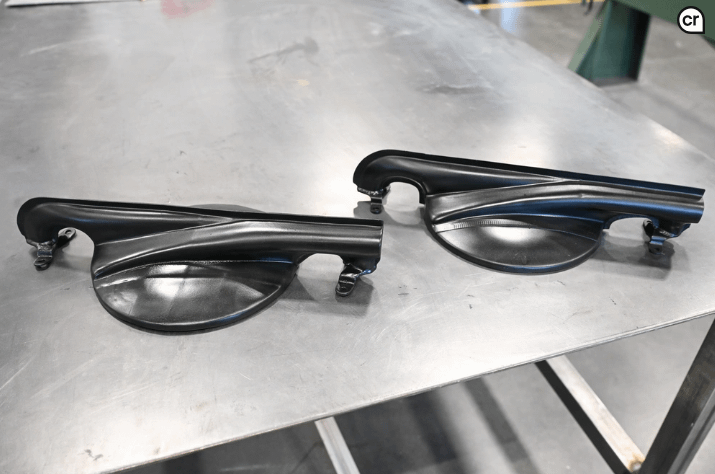

A 3D printed turbosupercharger cooling cap for a B-24 Liberator sits beside the original part at the Hill Aerospace Museum, Hill Air Force Base, Utah, Sept. 12, 2025. The museum’s restoration facility purchased 3D scanners and printers to support in-house preservation when original parts cannot be found.

There are many examples of 3D technologies being used to preserve history in the military and beyond, from battleship restoration and memorial preservation to recreating prehistoric species and ancient artwork. Now, at the Hill Aerospace Museum, to support the preservation of its historic aircraft, in-house 3D scanning and printing are helping the team recreate parts that are difficult to find, like the cooling cap pictured above and below.

A 3D printed turbosupercharger cooling cap for a B-24 Liberator sits in the upper turbosupercharger, with the original cap below, at the Hill Aerospace Museum, Hill Air Force Base, Utah, Sept. 12, 2025.

“Ensuring historical accuracy is at the forefront in restoration and exhibits. Our priority is to find the historically accurate part; if we are unable to find the correct part, that’s when we turn to modern technology to recreate our part for visual purposes,” explained Brandon Hedges, museum restoration chief.

Sometimes, you need to spend money to make money, or to save it. The museum recently invested $6,000 in the 3D technology, which has ultimately lowered project costs by 80%. 3D printing and scanning has also saved the team plenty of precious time, as it used to take them months to find obsolete components. Now, the authenticity of the museum’s historic aviation collection can be preserved, thanks to the accurately reproduced parts enabled by the technology.

Brandon Hedges, Hill Aerospace Museum’s restoration chief, shows a 3D printed part on an A-1 Skyrider flap Sept. 12, 2025, at Hill Air Force Base, Utah. The technology has delivered an 80% cost savings and saved hundreds of hours since the museum acquired the printers and scanners for restoration and exhibits.

“If we decide to 3D print something that we cannot find a surplus, we strive to make it blend in just as the original,” Hedges said. “Providing the visitors with historically accurate depictions is mission priority for restoration and exhibits.”

According to Hedges, work on a specific part for the museum begins with the team members researching the part. Then, they try to find an original, often starting by asking the aviation community for help. Once they’ve exhausted all avenues and still can’t find an original part, the team uses their gathered research, and scans of existing components, to determine the proper dimensions. Then, they use 3D scanning and printing to achieve an accurate replica, which improves the authenticity of the restored aircraft that visitors come to see.

“It takes careful adjustments, correct lighting, and steady movements to create the perfect model,” said museum intern Holly Bingham about the scanners the restoration team acquired to capture a part’s every detail. “These models can then be 3D printed to replace the fragile or missing components of a plane.”

John Sluder, Hill Aerospace Museum exhibit specialist, talks about one of the 3D printers the museum acquired to restore parts and to enhance exhibits Sept. 12, 2025, at Hill Air Force Base, Utah.

The museum’s restoration team tracks every part they recreate with 3D technology. That way, if they end up eventually getting their hands on an original, they can swap it with the 3D printed replica.

The 3D equipment isn’t just used for restoration of their historic aircraft, either. Hedges said multiple programs at the museum, such as education, curation, and exhibits, have been able to utilize the technology to save on money and resources.

John Sluder, Hill Aerospace Museum exhibit specialist, shows organization containers printed with 3D technology Sept. 12, 2025, at Hill Air Force Base, Utah.

“What excites me most is that 3D printing isn’t just helping us restore aircraft parts. It’s giving us tools to solve everyday challenges in the museum, from keeping exhibits safe to making signage more flexible,” explained exhibit specialist John Sluder. “In the end, it means we can preserve history more effectively and share the Air Force story with future generations in ways that are sustainable and adaptable.”

Sluder said that one of the museum’s most successful 3D printing projects was its static sign mounts. The mounts, which hold and display informational signs next to exhibits and aircraft, feature 3D printed feet to keep the steel base plates of the signs from sliding around on the concrete floor. Additionally, the fixtures for the mounts are also 3D printed, which makes it fast and easy to swap and reuse them multiple times.

John Sluder, Hill Aerospace Museum exhibit specialist, shows 3D printed parts printed for exhibit sign mounts Sept. 12, 2025, at Hill Air Force Base, Utah.

U.S. Air Force photos by Cynthia Griggs